The Missing Link in Supply-Side Economics

Why Human Capital Investment Matters

I wasn't born when Ronald Reagan was first elected president in 1980, but I remember hearing him on TV when my parents were completing their education in DC in the mid to late 80s. Years later, through my studies in economics, I would learn how pivotal those years were economically and socially. Reagan ushered in the era of supply-side economics and what would be coined as "trickle-down economics."

Today, as supply-side principles resurface in policy debates, including recent discussions around education legislation, it's worth examining what mainstream supply-side economists get right, what they miss, and how we can use other economic principles to design better policies that improve economic well-being for everyone.

Traditional Supply-Side Economics: The Basics

Supply-side economics focuses on boosting economic growth by increasing the supply of goods and services rather than stimulating demand. The core idea is that policies making it easier and more profitable for businesses to produce will ultimately benefit the entire economy.

The theory emphasizes three key mechanisms:

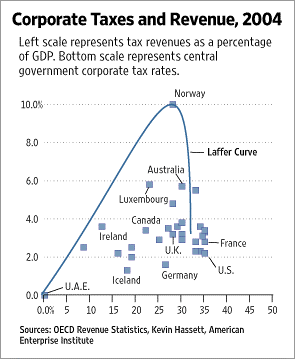

Tax policy is central to supply-side thinking. Proponents argue that reducing tax rates, especially on income and capital gains, gives individuals and businesses more incentive to work, save, and invest. The famous "Laffer Curve" suggests there's an optimal tax rate that maximizes government revenue; increasing it too high discourages economic activity, while decreasing it too low results in insufficient revenue collection.

Deregulation is another pillar, with the belief that reducing bureaucratic barriers allows businesses to operate more efficiently and allocate resources more effectively. This includes everything from environmental regulations to financial rules.

Investment incentives like accelerated depreciation schedules or research and development tax credits are designed to encourage capital formation and innovation, which supply-siders see as drivers of long-term growth.

The theory gained prominence during Reagan's presidency, earning the nickname "Reaganomics." Supply-side economists like Arthur Laffer and Robert Mundell argued that tax cuts would pay for themselves through increased economic growth.

Voodoo Economics

Critics argue that supply-side policies primarily benefit wealthy individuals and corporations, can increase income inequality, and that the promised economic growth often doesn't materialize sufficiently to offset tax revenue losses. Some went as far as calling Reagan’s policies “Voodoo Economics.” That was the term George H.W. Bush used to describe U.S. President Ronald Reagan’s economic policies before becoming his vice president. The former vice president believed that supply-side policies were not only going to fall short of stimulating the economy but that they would also drastically increase the country’s national debt.

The Missing Link: Human Capital Investment

Here's what traditional supply-side economics gets wrong: it focuses almost exclusively on capital and largely ignores the productivity of people. But the most dramatic economic growth stories of the past century weren't driven by tax cuts. Massive investments in human capital powered them.

South Korea

Consider South Korea's transformation. In 1960, South Korea's GDP per capita was lower than Ghana's. By 2020, it had become a developed nation with the world's 10th largest economy. South Korea invested heavily in primary education in the 1960s, secondary education in the 1970s, and higher education from the 1980s onward. By 2010, South Korea had the highest percentage of 25-34 year-olds with tertiary education in the OECD. South Korea became known as the "Miracle on the Han River".

This educational investment created a skilled workforce that could absorb advanced technology, innovate, and attract foreign investment. Samsung, LG, and Hyundai didn't become global leaders because they had access to increasingly skilled workers.

Singapore

Singapore tells a similar story. The city-state invested heavily in education and healthcare from its independence in 1965. Today, Singaporean students consistently rank among the world's best in international assessments, and the country has one of the world's most efficient healthcare systems. These investments in human capital helped Singapore become a global financial center and technology hub.

United States Post WWII

The United States followed this playbook after World War II. The GI Bill, which provided education benefits to returning veterans and massive investments in public education and research universities, created the skilled workforce that powered America's post-war economic boom.

What Modern Growth Theory Teaches Us

This insight aligns with what economists have learned about growth over the past 30 years. Economists like Paul Romer, Robert Lucas, and Philippe Aghion developed models where growth comes from within the economic system itself, particularly through:

Knowledge spillovers: When people get educated, they don't just become more productive individually; they also share knowledge with others

Learning-by-doing: Experience and education create cumulative knowledge that builds on itself

Innovation networks: Skilled workers cluster together and create innovation ecosystems

Investment in education and healthcare fits perfectly here through their effects on human capital and productivity. However, this relationship is more nuanced than traditional supply-side tax policy.

Education as a supply-side investment works by enhancing the quality and skills of the workforce. A more educated population can produce goods and services more efficiently, innovate more effectively, and adapt to technological changes. This increases the economy's productive capacity, which is the fundamental goal of supply-side policy.

Healthcare investment operates similarly by maintaining and improving worker productivity. Healthier workers are more productive, miss fewer days, and can work longer into their careers. Public health improvements also reduce healthcare costs for businesses, making them more competitive. The reduction in sick days and disability claims effectively increases the available labor supply.

The Takeaway

Supply-side economics isn't wrong; it's just incomplete. If you believe in supply-side economics, you should be thinking about how to increase the productivity of both capital and labor. The most powerful way to increase labor productivity isn't through tax cuts that might encourage a few more hours of work. It's through investments in education and healthcare that workers can dramatically improve what they can accomplish in those hours.

As we evaluate our policies, we must consider the source of innovation and productivity. After all, improving the economy means improving the well-being of the people who live in the economy. By providing them with the necessary tools, health, and incentives, they will innovate and continue to grow.

What are your thoughts? I would love to hear more about the policies you find crticial for economic success.

Stay informed,

Dr. A

Dr. Abdullah Al Bahrani is an economics professor and an award-winning educator. His research focuses on household finance and economic education. In addition to this newsletter, he has a YouTube channel and an Instagram account to share his economic insights. His goal is to improve economic literacy and well-being.

Supply side economics would be the first chapter in next book, "Lies Your Economics Teacher Taught You"

I was alive in 1980 ;-). Laffer's curve was perfectly valid -- the only question is at what top marginal income tax rate does income to government start to fall? The top marginal rate in 1980, when Reagan was elected, was 70% -- he reduced it to 50%. Top marginal rate for capital gains was 28% -- this was about when the trend to paying CEOs with stock options really got going (and when the practice of CEOs manipulating stock prices became a problem). It is useful to remember that the top marginal rate when John Kennedy was elected in 1962 (I was alive then too ;-)) was 91% -- he reduced it to 70%. A consensus figure among economists for the top of the Laffer Curve (on the basis of evidence, not mere assertion) is 65 or 70%. Fill in the dots... Oh, and while we are on the subject, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez' proposal for the top marginal rate is... 70%, including capital gains. Not that I am necessarily a proponent of maximum realistic income redistribution...