U.S. Manufacturing Myths

The "Decline" of Manufacturing isn't the real issue

This week, I want to challenge a persistent narrative that has shaped economic policy discussions for decades: the supposed "death of American manufacturing." This misconception has led to misguided policy proposals, nostalgia-driven economic strategies, and a fundamental misunderstanding of what our economy needs to thrive in the 21st century.

The Manufacturing Reality Check

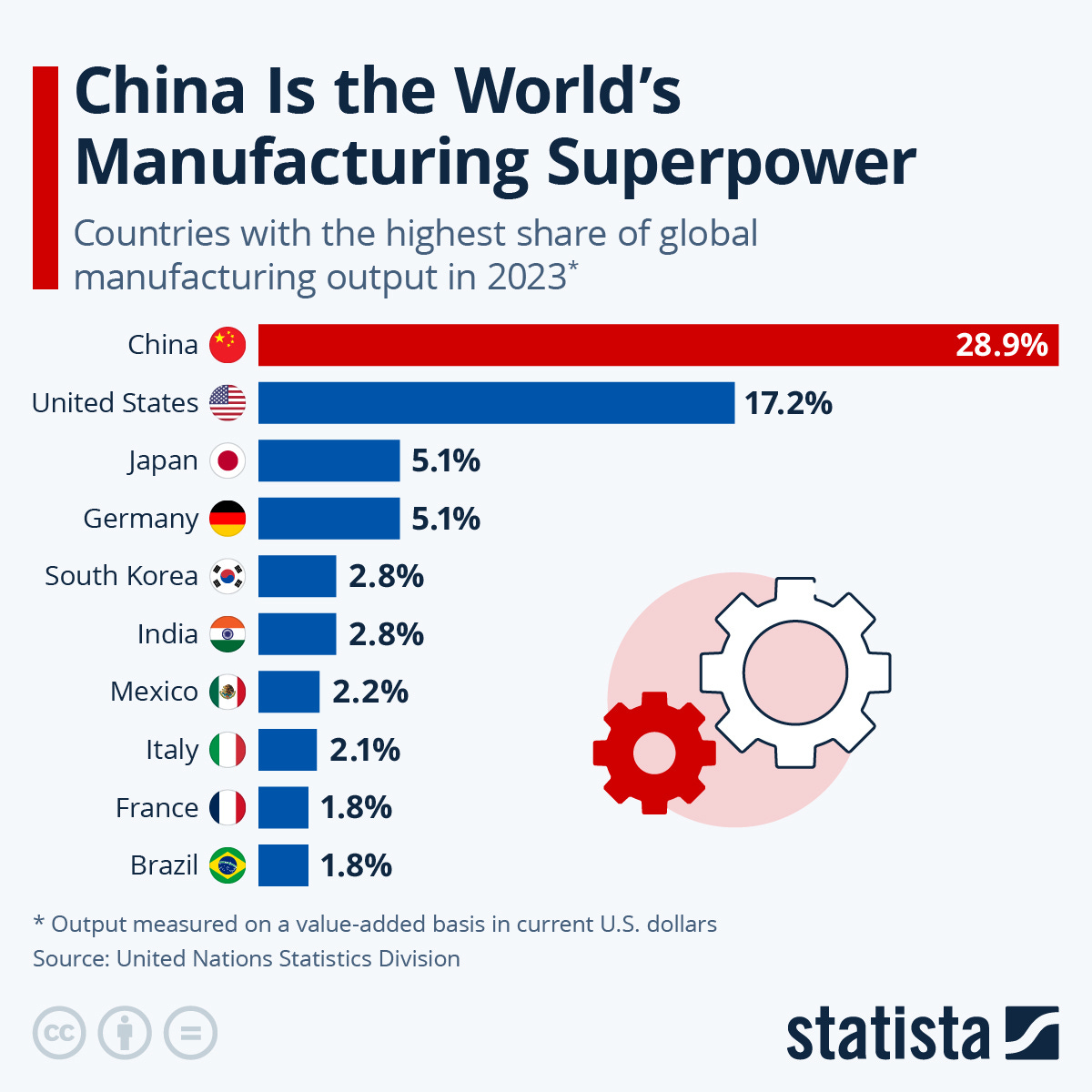

What if I told you that if we worked hard, the U.S. could become the second-largest manufacturing country in the world?

You don't have to wait—we already are.

The United States is firmly established as the world's second-largest manufacturing nation. But that's not all. We're also dramatically more efficient than China, the only country that outproduces us. American manufacturing generates approximately three times the output per worker-hour compared to China.

We manufacture a lot, and we do it extremely well. The reality is that manufacturing isn't a diminishing sector in terms of output—it's just not as labor-intensive as it once was.

Why The Perception Gap Exists

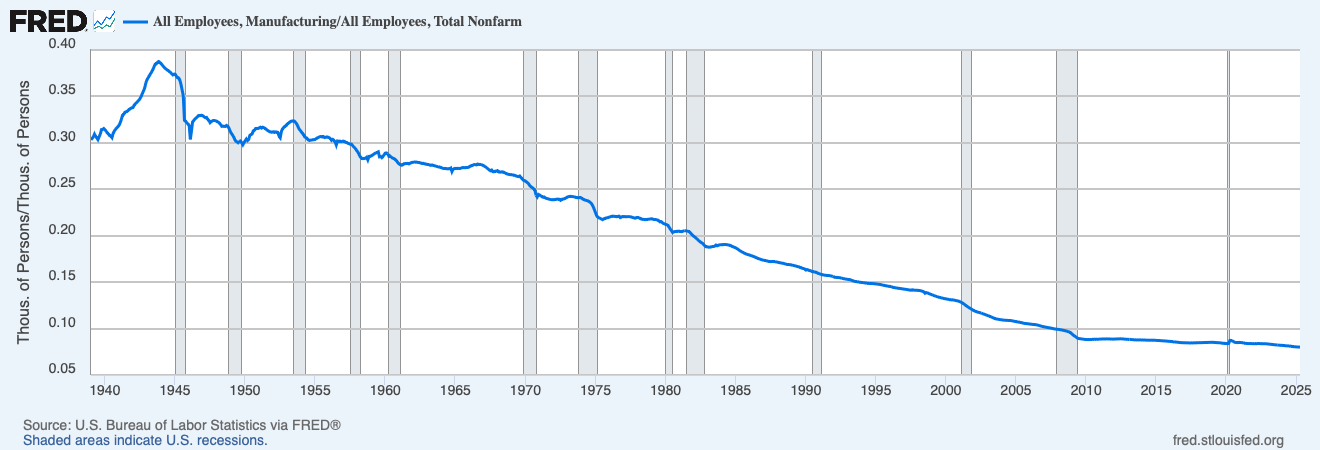

I understand why many Americans feel manufacturing has disappeared. After all, manufacturing employment has fallen from about one-third of nonfarm employment in the early 1950s to less than one-twelfth today. This dramatic shift in employment patterns has created economic dislocation, particularly in regions once dominated by manufacturing.

But this decline in manufacturing employment doesn't reflect a decline in manufacturing output. U.S. manufacturing output actually rose, after adjusting for inflation, during the 1970s and 1980s—decades often associated with the beginning of "deindustrialization."

When people worry about manufacturing in America, they're frequently worrying specifically about manufacturing jobs, not manufacturing itself. The manufacturing that got outsourced typically represents low-wage, low-skill production, like clothing assembly or basic component manufacturing. If those operations had remained in the U.S., our high-wage economy would likely have accelerated automation to remain competitive.

Keeping those manufacturing jobs in America would have required not just trade barriers but also suppressing innovation and the adoption of labor-saving technologies—a strategy that would ultimately weaken our economic position, not strengthen it.

The Agricultural Parallel

To put this in perspective, consider agriculture. In the late 1940s, approximately 14% of American workers were employed in farming. Today, that figure is less than 2%. Yet, American agricultural output has soared to record levels.

Should we lament this transition and advocate for policies that would return millions of Americans to labor-intensive farming? Few would suggest this makes economic sense. We recognize that technological advancement in agriculture has been a net positive for our economy and society, even as it dramatically reduced the sector's employment share.

Manufacturing has followed a similar trajectory. The difference is that we seem to view the agricultural transition as progress while viewing the manufacturing transition as decline.

The Real Challenge: Adapting to Change

The core issue isn't that we're manufacturing less—it's that our economy has evolved faster than our workforce development systems and social safety nets.

During the 1980s and 1990s, as manufacturing became more efficient and required fewer workers, we needed a stronger push to reskill workers and prepare them for emerging industries. This would have required robust educational programs, incentives for training and development, and support for geographic mobility.

Instead, in cities where manufacturers departed, workers were often left with obsolete skills and few pathways to transition into growing sectors. The problem wasn't manufacturing decline—it was our collective failure to manage economic evolution.

Americans have historically been reluctant to relocate across state lines, even when economic opportunities would improve by doing so. This limited geographic mobility, combined with inadequate skill development programs, created pockets of economic distress that persist today.

The Path Forward: Building Adaptive Labor Markets

Rather than chasing the impossible goal of returning to manufacturing-dominated employment, we should focus on creating labor markets that are nimble, skilled, and adaptable to inevitable economic shifts.

This requires:

Education systems aligned with economic reality: We need educational pathways that prepare workers not just for today's jobs but for careers that may evolve significantly over decades.

Continuous skill development: The notion of learning a single trade and practicing it for life is increasingly obsolete. We need systems that support ongoing skill development throughout careers.

Development of transferrable skills: We need to help develop workforce skills that can transfer to new industries and evolve with market needs.

Geographic mobility support: When industries decline in specific regions, we need better mechanisms to help workers relocate to areas with stronger opportunities. Alternatively, economic development organizations need to continuously plan ahead to attract new industries.

Stronger transitions: When industries evolve, we need programs that help workers bridge to adjacent or emerging sectors without extended unemployment.

Reality-based economic narrative: We need to stop feeding the myth that manufacturing decline is America's core economic problem. Our challenge is adaptation, not restoration.

The Takeaway

America doesn't have a manufacturing problem—we have a transition problem. Our manufacturing sector continues to produce enormous value with remarkable efficiency. What we've struggled with is helping workers navigate the shift from manufacturing employment to other sectors.

The nostalgia for a manufacturing-dominated economy reflects a legitimate concern about economic security and quality of life for working Americans. But the solution isn't to reverse technological progress or globalization—it's to build systems that help workers thrive amid inevitable economic evolution. Holding on to the hope of returning to the “ old days” is harmful and only works to slow down the pace of innovation and transition. Our policies need to facilitate change, not hinder it.

When we misdiagnose manufacturing output as our problem, we create policies that attempt to solve the wrong issue. Instead, we should focus on the real challenge: building an economy where workers can adapt to change without experiencing devastating disruption to their lives and livelihoods.

Thank you for reading. I would love to hear your thoughts on this topic.

Please share this post with the person who says manufacturing is dead in America or that we need to bring back manufacturing in the U.S.

Dr. A

"Economics with Dr. A" is a newsletter dedicated to explaining the personal side of economics. Subscribe to our mailing list for in-depth analysis, historical context, and practical guidance for navigating our complex marketplace.

Share the Knowledge: If you found this perspective on manufacturing valuable, please forward it to friends and colleagues who might be stuck in outdated economic narratives. Sometimes the first step toward better policy is developing a more accurate understanding of our economic reality.

Great description of the issue.

Regarding the education point/skill transferability, I remember a great anecdote about from my liberal arts college, where the person who also completed the degree at the same liberal arts college, explained that one major benefit of the education they got at the college was the ability to shift from very wildly different - sports to management to administration, which was thanks to the liberal arts education.

Today, I still see a lot of posts criticizing the concept of liberal arts studies as 'not focused' or 'unemployable', but in the long run of one's career, I think a broad education is necessary.

Great letter. You are definitely right about mobility. That is the largest issue to date. It also persists in other western countries also. The problem in my eyes is congress will never pounce on it and states will not collaborate to resolve it on their level.

The solutions are out there the issue is getting people to move forward with it.